CLOs Explained (Well, Sort Of…….)

There is a lot of commentary here on Seeking Alpha about CLO funds and exchange-traded funds (“ETFs”). This is not surprising given some of the huge distribution yields paid out by closed-end funds (“CEFs”) like Eagle Point Credit Co LLC (NYSE:ECC) and Oxford Lane Capital Corporation (NASDAQ:OXLC), which currently yield 17% and 19% respectively.

CLOs, for the uninitiated, are “collateralized loan obligations,” which are structured vehicles created to buy and hold corporate loans, which are senior, secured, floating rate, and sit at the very top of the corporate issuer’s liability structure. In other words, loans are the safest security, from a credit standpoint, that corporations issue, since they are entitled to be fully repaid, in a corporate default, bankruptcy or reorganization, before other debt (like unsecured bonds or convertible debt) or stockholders receive any payment.

Another way to think about and understand CLOs is to imagine they are “virtual banks.” Just like a bank, they fund themselves with debt (which in the case of a real bank would mostly be called “deposits”) and with equity. Again, just like a real bank, a CLO’s deposits exceed its equity by about 9 to 1. That means CLO equity, just like the equity of JPMorgan (JPM) or Citigroup (C), is highly leveraged.

This leads to a certain amount of confusion among some readers – and even some authors here on Seeking Alpha – who (judging by their comments and occasional articles) don’t always seem to realize that while the loan assets that CLOs hold are well secured and relatively safe, as investments go, that doesn’t mean the equity of the CLOs that hold those loans is equally safe. One of the reasons that corporate loans are so safe is because they are secured and they get paid first in a corporate default or bankruptcy, before the debt and equity under them gets paid. It’s that debt and equity under them that serves as a “cushion” to take all the losses, so the loans and other debt closer to the top get paid in full.

It’s the same in a CLO, where most of the debt issued by the CLO itself is actually very safe, but that’s only because CLO equity at the bottom of the CLO takes all the losses; and in the very rare cases where losses have been great enough to eat through the CLO equity tranche, the remaining loss would be absorbed by the CLO’s lowest debt tranches (the double BB tranche and in extremely rate cases, the BBB tranche).

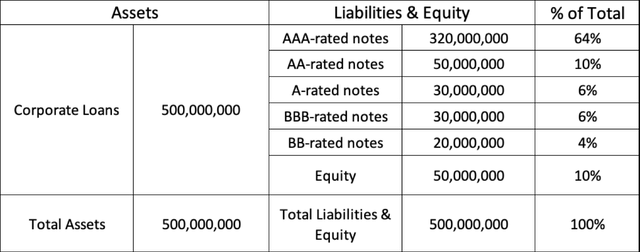

Here is the typical capital structure of a CLO:

The total assets consist of $500 million of senior corporate loans. Financing the CLO is $450 million of debt, layered in a number of “tranches” which rank one above the other in terms of “seniority” (i.e., the order in which they get paid in a liquidation), with equity of $50,000 at the very bottom of the capital structure.

Like equity in all corporations, the CLO equity owners (funds like ECC and OXLC, and a recently launched new one, Carlyle Credit Income Fund (CCIF), as well as institutional investors of all kinds) get the excess profits from the portfolio, after interest on the debt is paid. The potential profit is substantial, since the loans pay an average coupon substantially higher than the weighted average cost of funds that the CLO pays on its debt.

That “spread” or margin between the yield on the loans the CLO owns and the average cost of its debt (i.e., its 9 times leverage, in this example) all flows down to the equity owners. So, if the yield on loans were, say, 7% and the average cost of funds were 4.5%, the 2.5% margin would be leveraged 9 times, so the equity would collect 9 X 2.5%, or 22.5%. It would also collect the full 7% on the amount of its capital invested, since there would be no cost of debt to deduct from that; so the total gross margin earned by the equity in that case would be 22.5% plus 7% = 29.5%.

If that’s all there was to it, we’d all invest all our money in CLOs. Of course, there is more to it than that, since the equity, besides having to pay all the expenses of managing the CLO, also has to absorb all the credit losses from the entire portfolio. Just like a bank. Obviously, if you are a depositor at a bank and the bank suffers some losses on its loans, it doesn’t deduct the losses from your checking account. They are deducted from the profits of the bank, and the financial hit is to the shareholders.

Same with a CLO, so suppose the loan portfolio suffers a 2% default rate in a year, and loans, because they are secured, have historically collected 60% recoveries in the event of default (actually more, but we’ll be conservative and assume 60%). That means the loss per defaulted loan would be 40%, and the loss on the whole portfolio would then be 40% times 2%, or 0.8% of the portfolio. That 0.8%, with leverage of 9 times, would represent a 7.2% hit to the equity.

We saw in our example up above the CLO’s gross margin was 29%, before credit losses and other expenses. So it could take a hit of 7.2% and still have a gross margin well above 20%.

This example demonstrates how robust the CLO structure can be in generating high returns. But it also shows how sensitive those returns can be to credit losses wiping out those returns, if such losses were allowed to get out of control. Ares Management, along with quite a few others, has published some excellent research on CLO returns and the factors that affect them. In particular they show that CLO managers, perhaps because they focus so intensively on loans and active trade their portfolios, have consistently had much lower default rates than the overall institutional investor population. Their research helps to explain why CLOs have managed to do well through a variety of economic cycles over the past 30+ years since they were first introduced.

More Than Just Interest Rate Margin

Ironically, CLOs often do better, and make more money for their equity owners, during volatile periods when markets are nervous about the credit and/or economic outlook (which is the environment we have been in for the past year or two). During times like this the market prices of loans drop, sometimes to the low 90% range as they did a year or so ago, although they are in the mid 90s currently. That means when CLOs collect maturing loans, they can reinvest the proceeds in new loans bought at discounts on the secondary loan market. So they can buy a loan at say, 95 cents on the dollar, collect, say, a 7% coupon (that’s 7% of par, 100 cents on the dollar), which works out to be a higher yield as a percent of the 95 cents the CLO paid for it. Better yet, when the loan matures in a couple years, the CLO collects the repayment at par, so there is a 5% capital gain on top of the yield.

This makes for some interesting gyrations and seeming inconsistencies between CLO net asset values and the actual business prospects of the CLOs themselves. In other words, when loan prices drop on the secondary market, a typical CLO’s loan portfolio would be marked down to the lower market price. Obviously its own debt wouldn’t be affected, since it still owes its creditors the same amount, regardless of whether its loan assets go up or down in price. So its equity would be written down to reflect the drop in the loan assets’ value. But those loans would still be generating the same income; and in addition they’d be cheaper and, as just described, the CLO could buy “replacement” assets at lower prices than ever, locking in future capital gains.

This is why, as we have written on various occasions, a drop in CLO value (or the NAV of a fund that owns CLOs) is not necessarily negative, if it actually evidences opportunity for CLO managers to increase their profits in the near term.

CLOs and Closed-End Funds

Up until now, we’ve talked mostly about CLOs. When you add the additional complexity of holding the equity and/or debt of CLOs in closed-end funds, the topic becomes even more complicated. It’s only been a little more than a decade since CEFs, the first being OXLC and then a few years later ECC and some others, made CLOs available to retail investors.

I think we’ve come a long way up the learning curve, both as writers and as investors, in understanding CLOs and the funds that hold them, but I also think we have a long way to go. Because I worked in credit much of my life, as a banker, a journalist, and later at Standard & Poor’s where I introduced credit ratings to the previously un-rated corporate loan market, I had a head start in understanding CLOs. But I’m still struggling to understand the inner workings, both tax-wise and accounting-wise, of the funds we hold. Especially how to understand the extremely generous distributions, and to know how much is covered by current income and how much represents current or future price erosion.

For example, here are some highlights from ECC’s most recent announcement (August 15) of its 2nd quarter results.

- “Net investment income (“NII”) of $0.32 per share.” That’s pretty straightforward and we are accustomed to comparing NII to a fund’s distribution rate per share to see whether the fund is covering its payout with cash flow (NII = dividends and interest payments received, minus fund expenses). If it isn’t, then we know the fund is dependent on capital gains or other income to make its distribution payments.

- We know that ECC has recently been paying a monthly distribution of 16 cents per share, which would mean its quarterly distribution was $0.48 per share. So reading just this far, we’d see that ECC’s NII coverage ratio of its distribution was 32 cents/48 cents, or two/thirds (i.e. 67%).

- That’s not bad, especially for funds that also earn capital gains as a regular part of their strategy. But then we read that ECC actually incurred capital losses during the quarter, so that its GAAP income (which includes NII plus capital gains and losses) was only $0.11 per share.

- On its face, that might raise concerns, especially if it were a consistent, ongoing trend.

- But then in the next line we are told that the fund received $0.90 per share in “recurring cash distributions,” which was well in excess of the fund’s cash distributions (i.e., 48 cents per share) as well as the fund’s expenses.

- There is also a chart that appears regularly in ECC’s quarterly investor presentation (page 23) showing these “recurring cash flows” in comparison to their ongoing dividend payment.

- Clearly the message is that it is “recurring cash flows” received from their CLO portfolio, and not merely the NII component of those cash flows, that investors should focus on.

- But since NII includes the interest component, what else is in the “recurring cash flows?” My guess is that a large component of it would be amortizing principal payments that are made by the borrowers each month or quarter along with their interest payments. Corporate loans often have regular amortizing principal payments made over the term of the loan (like your home mortgage) as well as a balloon payment of whatever is still owed at the end of its term, which might be 5, 7, 10 years, or whatever.

- If that is what is happening, it would be consistent with how I understand CLOs work, where whatever payments CLO managers receive from the loans in the CLO’s portfolio are used first to service their own debt (top tranches first, then a waterfall of payments down to the lower tranches) and finally whatever is left is paid to the equity.

- Bottom line: if part of the distribution that ECC routinely pays out consists of amortizing principal payments that are part of the regular cash flow it receives on its CLO equity investments, then clearly it must be a return of capital and represents a reduction in the principal on those loans that will be received at their final maturity.

- Offsetting this capital erosion (at least in part) may be capital gains that the CLO managers earn from trading their portfolios, buying new loans at discounts (as described earlier) and generally taking other steps (like renegotiating and extending CLO debt, “re-setting” the CLO itself to extend its reinvestment period) that have the effect of what CLO experts call “building par.”

None of this makes me believe that CLOs or funds that hold them aren’t good investments, and personally I own plenty of them in my personal portfolios. But it does tell me that CLO fund managers and sponsors have a long way to go to find ways to simplify and explain their products so typical retail investors can better understand them.

Meanwhile, I would assume that the very high yields that funds like ECC, OXLC and other CLO equity funds are paying contain a considerable amount of loan principal return that may end up eroding the fund’s net asset value at some point in the future. In the meantime, in order to offset any erosion in my own portfolio, I am making a point of reinvesting most or all of the distributions I receive.

My purpose here is NOT to run down CLOs or the funds that hold them, because I think it’s a fine asset class. But I hope, through discussion and raising the right questions, that we can encourage the funds themselves to become more transparent and to learn how to be better at explaining themselves to their investors.

Editor’s Note: This article covers one or more microcap stocks. Please be aware of the risks associated with these stocks.

Read the full article here