If your idea of train travel – fast, easy, ubiquitous, even glamorous – is from movies like “Before Sunrise” or “Bullet Train” set in Europe or Asia, you’ll be surprised to learn that the US was once the world’s superpower in passenger trains. With a busy transcontinental network of 254,000 miles of tracks at its height a little over a century ago, America moved on trains.

Today, the United States’ passenger rail system is an echo of its former self, with swathes of the network unused or surrendered to freight. Over the last century, the United States shifted its focus – and investments – away from passenger railroads and toward travel by cars and planes.

That may be starting to change. Efforts to revive railroad travel in the US have recently picked up steam amid a push to lower emissions: Earlier this month, the Biden administration announced that the federal government would pump $16 billion into improving the nation’s busiest rail line, Amtrak’s Northeast Corridor, which runs from Boston to Washington, D.C.

Brightline, the country’s only privately owned and operated intercity railroad, opened its completed train line between Orlando and Miami in September. Its roughly three-hour run shaves about an hour off of drive time. California has invested heavily in a route from Los Angeles to San Francisco.

The time might be right for a railroad renaissance. The Swedish “flyskam” movement, which translates to “flight shame,” has grown worldwide among people seeking to diminish their carbon footprints. The transportation sector emits the highest amount of greenhouse gas of all US sectors – and the US Department of Transportation has said that rail could play an essential role in reducing emissions.

Traveling by train is not entirely out of fashion in the US. Today, Amtrak is the main provider of intercity rail travel; the government-owned system runs on more than 21,400 miles of track and operates in 46 states.

But the US has a long way to go, experts say, to catch up to countries like France, Japan and China when it comes to high-speed rail and wide-reaching train travel.

The rise and fall of US trains

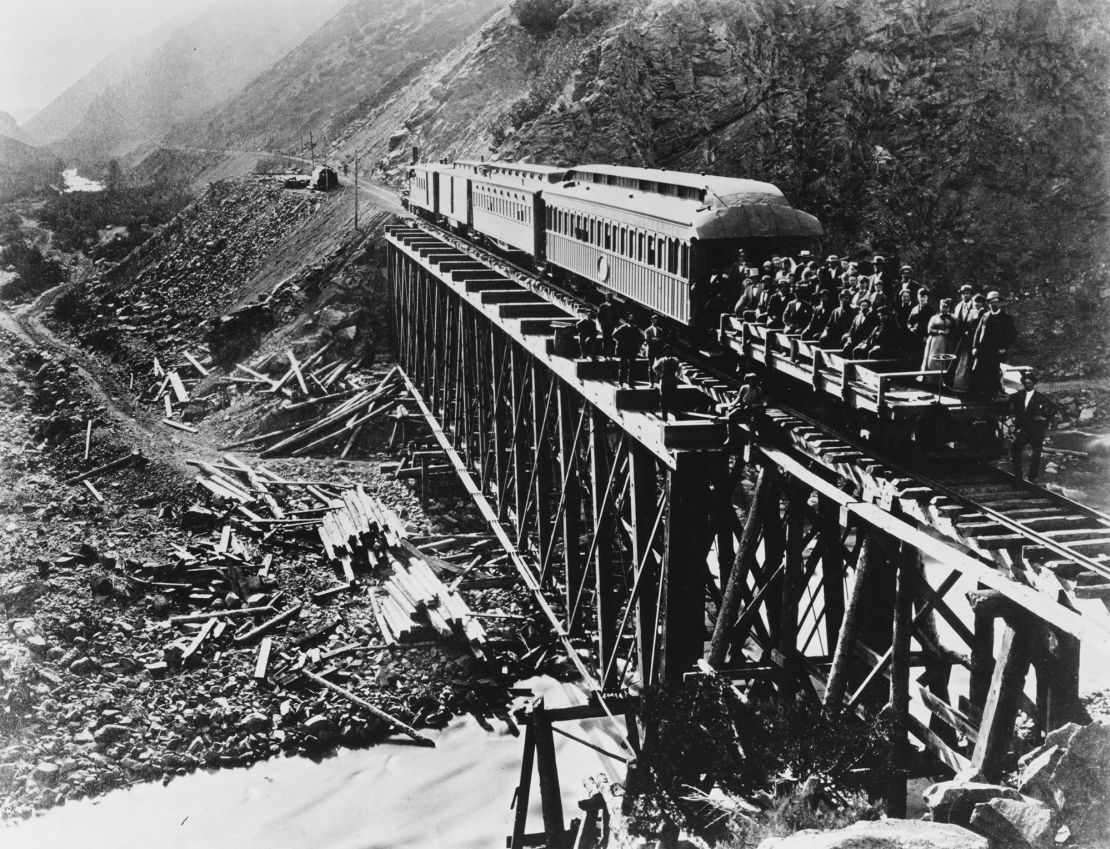

In the 19th century, trains revolutionized how people traveled, and the US led the way. Some of the nation’s greatest fortunes – those of JP Morgan, Jay Gould, Cornelius Vanderbilt, among others – were built on the rails. By the 1860s, private US companies, with the help of government cash and land grants, were constructing the country’s first transcontinental railroad. It connected the United States’ existing eastern rail network all the way to San Francisco in 1869. At the time, it was the longest railroad in the world and helped the US population expand westward, railway expert Christian Wolmar wrote in his 2012 book, “The Great Railroad Revolution.”

In exchange for government subsidies, rail carriers were required to provide passenger service. Train travel became ubiquitous, Wolmar notes, and by the 1900s, almost every American lived within easy access to a train station.

Today, much of the train tracks once used by passengers are now used exclusively by freight trains – and for many Americans, train travel isn’t even a consideration. So what happened?

While there is no single answer, Yonah Freemark, the Urban Institute’s lead on the fair housing, land use and transportation practice area, told CNN that one primary reason for passenger trains’ decline in popularity was that the nation diverted its attention to a newer, flashier form of transportation: cars.

Freemark said the US government began encouraging states to invest in highways in the 1920s. Those efforts accelerated under President Dwight D. Eisenhower.

According to the website of the United States Senate, which provides a history of legislation, Eisenhower’s interest in the US highway system dated back to his participation in the Army’s first cross-country motor convoy in 1919. It gave him first-hand knowledge of the poor quality of America’s roads. In his State of the Union message in 1954, he proposed an American interstate highway system, which he justified as a national defense program. The highways could be used for transporting troops and for evacuating cities in case of nuclear attack.

While the government’s encouragement of highway travel wasn’t solely a US phenomenon, “the difference between the US and other countries is that the US essentially allowed the private passenger rail companies to slowly disappear into irrelevance,” said Freemark.

“We created an environment in which it was difficult for railways to compete with the car,” he added.

Paul Hammond, a historian and the executive director of the Colorado Railroad Museum, said poor timing played a factor as well. Railroad companies invested heavily in newer modern equipment after World War II just as the postwar baby boom and suburban living grew in popularity. Hammond said: “Railroads sunk a lot of money into modernizing the passenger network right at the wrong time.”

By the early 1970s, passenger rail service had become a drag on private companies’ bottom lines amid low ridership, deteriorating infrastructure and growing competition from cars and planes.

In 1970, President Richard Nixon signed the Rail Passenger Service Act, which removed the requirement that private rail companies provide passenger service. The US government created Amtrak.

While the organization is much smaller than similar government-owned agencies in many foreign countries, Amtrak serves more than 20 million passengers annually.

But many American towns and cities have lost access to passenger trains. Since 1971, some routes have been abandoned, primarily in midwestern states like Indiana and Ohio, according to route maps provided by the Bureau of Transportation Statistics.

Amtrak also has little control over scheduling delays and on-track maintenance, since more than 70% of the tracks it runs on are owned – and shared – with private freight companies.

Amtrak’s affordability poses an issue, as well, according to Freemark. “They charge prices that are much higher than you see in other countries with much better service,” he said.

However, some improvements are on the way. In early November, the Biden administration announced plans to improve Amtrak’s Northeast Corridor, the system’s most heavily used route.

Federal funds will go toward the safety of the trains, expanding capacity for more riders and replacing aging infrastructure – including a Baltimore rail tunnel that opened while Ulysses S. Grant was president.

“I know how much it matters,” said President Joe Biden, who famously took Amtrak trips between Washington DC and his home in Delaware throughout his career in the Senate.

Though Amtrak’s Northeast Corridor introduced trains that could travel up to 150 mph in 2000, the organization is still far off from the high-speed trains seen in China and Japan that travel more than 200 mph. Most of the private companies that share tracks with Amtrak are hesitant to disrupt their operations to allow for updates, Freemark said.

A lack of political will has played a role, too. “The federal government’s commitment to investing in high-speed rail lines has been limited at best,” Freemark said.

It’s unlikely that train travel will recover the ground it lost. Since the age of railroad domination in the United States, the country has grown larger and more spread out.

A realistic goal would be to build out rail systems that link major metropolitan areas with economic connections, emulating Amtrak’s Northeaster Corridor, said Robert Puentes, the CEO of the Eno Center for Transportation, a nonprofit think tank.

“It’s not a ‘if you build it, they will come’ type of scenario,” Puentes said. “It would actually be fitting a need.”

Puentes said a good example of a potentially successful high-speed rail connection would be between Los Angeles and San Francisco. “It’s two metropolitan areas with a very strong economic connection between them; people travel there all the time, and it’s about the right distance for rail versus aviation,” he said.

However, while California has invested heavily in the route, it is taking longer than initially planned.

Private companies have attempted to step in and fill the void, too.

Brightline said it has welcomed millions of passengers aboard its South Florida trains and announced plans to break ground on another passenger railway between Los Angeles and Las Vegas.

Other private companies, like California-based Dreamstar Lines, are trying to restore romance to train travel. The company has announced plans to build a luxury overnight sleeper train that will run between Los Angeles and San Francisco.

Amtrak’s own sleeper cars have existed since 1979, but earlier this year, it kicked off a process to replace and update its overnight train fleet for the first time in four decades.

“We believe in the future of our long-distance service and we look forward to enhancing the customer experience across the Amtrak network,” Amtrak board chair Tony Coscia said in a January statement.

One challenge to the rail revolution will be convincing Americans to hop on trains rather than taking the cars they’ve grown accustomed to over generations.

“People just aren’t used to taking trains in the US,” Freemark said.

Read the full article here