There’s a dream solution to America’s housing crisis and to its increasingly deserted downtowns: Convert the empty offices into homes.

Across the country, cities like New York, Boston and Cleveland are embracing the idea of residential retrofitting and providing incentives to do so. The Biden administration is easing the way with federal programs and tax breaks. Local leaders are accelerating changes to zoning and construction restrictions.

But will turning offices into homes actually work? And would you want to live in one?

Experts in housing, building, and urban planning say it may be difficult to convert office space to livable, likeable residential housing, but there’s an urgent reason they’re trying.

More office space is sitting empty in the United States than at any point since 1979, Moody’s Analytics reported earlier this week. It’s all a hangover from the Covid-19 pandemic; employees started working remotely and never came back in full force, creating “zombie towers.”

Meanwhile, the US has lagged behind by about 5.5 million housing units over the past 20 years, according to the National Association of Realtors, as builders failed to keep up with housing needs.

So can we just convert the excess offices into needed apartments?

“If only it were so easy,” said Harold Bordwin, principal and co-president of Keen-Summit Capital Partners, which handles commercial real estate restructurings. “Unfortunately, there are a whole range of hurdles.”

There’s no formula or scalable model for turning an office into a home, said Brett Theodos, a senior fellow with the Metropolitan Housing and Communities Policy Center, part of the Urban Institute. “Every project has to reinvent the wheel,” he said, calling it “much harder than building from scratch.”

Here’s four reasons why it’s so hard.

Bureaucracy and restrictive zoning

Urban construction is ruled by zoning laws, which, at their most basic, follow a simple concept: only one kind of building – such as factories, apartment buildings, single-family homes – per part of town.

Such laws grew up in the post-World War II era and paved the way for the 1950’s American ideal, the home with a front porch and backyard a drive away from work. But unwinding those restrictions isn’t easy.

For builders, overturning zoning laws, on top of complying with dozens of building codes, can be a time-consuming and cost-prohibitive process.

“There are lawsuits, politics, and other property owners who will have a say,” Bordwin said. “Real estate is an open public process, as it should be. But when you say to a developer that the process is going to be slow and there’s a risk of litigation – that will make it more expensive.”

“Zoning is a speed bump,” said Theodos. “But mayors are tripping over themselves trying to remove that problem. They are trying very hard to make their downtowns viable, and this is something they can do.”

Cities have to worry about the tax revenue implications, though, since a decent share of revenue comes from commercial property taxes. Often cities cannot afford to lose the tax base of large office buildings.

And an apartment building, even if it’s full, is lower density use than an office. That means fewer people on the street, fewer people at lunch spots and, for cities, less tax revenue.

Sometimes former office locations can be good places to live, especially in high-density cities and areas with soaring demand for residential housing like Manhattan. In other cities, though, there may be no nearby stores, no schools, no public transit. How can you invent a neighborhood?

“A good amount of our office space is in suburban office parks that aren’t really attractive as a place for high density apartments,” said Theodos. “Maybe if you demolished and started fresh you could build some townhomes. But the street grid isn’t like a residential plan. They aren’t where people want to live.”

Cities, desperate to increase housing options for residents and revitalize their downtowns, have found that areas adjacent to the city’s core, but not in the suburbs, present good opportunities.

Cities with a higher-than-average rate of conversions typically have older office buildings with higher vacancy rates, according to CBRE, a commercial real estate services and investment firm. Cleveland has the highest percentage of its office stock targeted for conversion in the US at 11% of total inventory, while Boston has the largest square footage of conversions in the US planned or underway at 6.1 million square feet, or 3% of its office inventory.

Building design and structural hurdles

Not enough bathrooms. Not enough windows. Windows that don’t open at all.

By some estimates, only 3% of New York City office buildings and 2% in downtown Denver are suited for residential conversions.

Office space and homes are two fundamentally different types of buildings, according to builders and architects. Problems include a lack of natural light, the need for individual controls for heating, and ceiling heights that make electrical and HVAC retrofits impossible.

The square footage of commercial buildings has been growing larger ever since air conditioning became common in the mid-20th Century. Before air conditioning, buildings had a lot of windows that opened up, said Bordwin, adding that the leaseable square footage per floor for buildings of that era can be 5,000 to 15,000 square feet. Now, they can be 15,000 to 40,000 square feet.

“There are windows, but they are far away from the inside space,” said Bordwin. “It becomes a cave if you put walls up.”

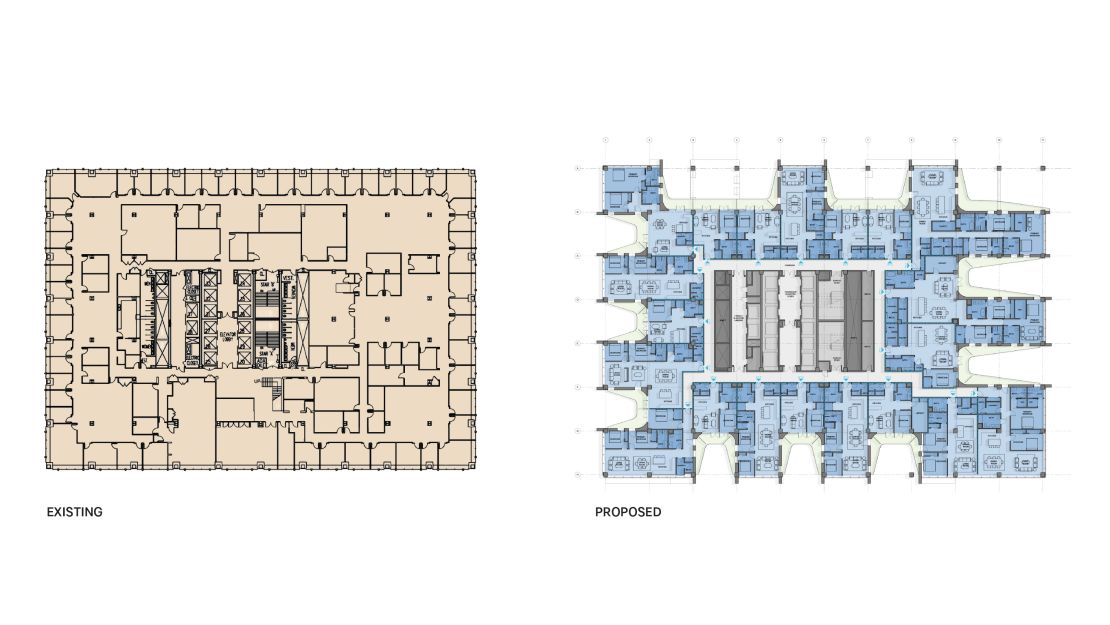

Maren Reepmeyer, a Boston architect with SGA who specializes in adaptive re-use projects like office to residential conversions, said that buildings with larger floors are much harder to convert. “As an architect it is really fun to think of ways to solve for that – carve out the inside with nooks and crannies, punch out a light well, create a courtyard, add little balconies. But they cost money.”

According to the CBRE Group, which tracks the real estate industry and investments, the costs associated with making those physical changes can range from $100 per square foot to over $500 per square foot, depending on the details of the building design.

Many “zombie” offices aren’t available for conversion yet: Tenants with long leases are still renting in even mostly empty buildings.

Consider one of the tallest skyscrapers in Chicago. Three major tenants are expected to be leaving the 65-story building at 311 South Wacker Drive, Crain’s Chicago Business reported this week. But their exits would still leave the tower 50% leased, and ineligible, for years at best, for conversion to housing.

Some landlords and developers looking to “activate” their building – and take advantage of government incentives to do so – can be stymied because of existing tenants.

“Maybe they are 50% leased,” said Reepmeyer. “That is tough. You’re not close to full. But what do you do with those existing tenants? Can you displace them? Do you have another building where you can move them?”

As result, according to Theodos, office conversions are not a solution to either the empty office glut or the housing supply shortage.

“I don’t expect residential conversions to be game-changers to office vacancy rates or apartment shortages in major cities so much that rents drop,” Theodos said. “On the other hand, when you add 600, 800 units through conversions over a few years in a mid-sized city, it isn’t nothing.”

– CNN’s Nathaniel Meyersohn and Donald Judd contributed to this article

Read the full article here